Blog post

Q&A with transplant nephrologist Dr. Silas Norman

In honor of Black History Month, and as he nears the end of his term as chair of AKF's Board of Trustees, the American Kidney Fund (AKF) is celebrating Dr. Silas Norman, a transplant nephrologist who has worked throughout his career to advance health equity and advocate for improvements to health care and quality of life for people living with kidney disease.

Born and educated in Detroit, Dr. Norman has been at the University of Michigan since 2002 working as a nephrologist in the transplant program. Dr. Norman has made a number of contributions to the transplant program including the creation of a program to transplant HIV-positive individuals and the development of outreach satellite clinics to allow patients greater access to transplant opportunities.

In addition to his work with AKF, Dr. Norman has served for over a decade on a number of committees of the United Network for Organ Sharing, including the Kidney Transplantation and Minority Affairs Committees, and is active with the Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program (MOTTEP) Detroit Foundation Board.

Get to know more about Dr. Norman in this Q&A.

How did you become interested in a career in medicine?

My father was an internal medicine physician and when I was getting ready for college, I thought I would also be a physician. I think I was going into primary care, in part because I thought I understood what my father did (which of course at 17 I didn't) … I had this broad idea that I would become a doctor, open a private practice in the community and take care of people with diabetes and high blood pressure. And then once I got into medical school, I rotated with a couple great physicians who were internal medicine physicians and thought that's what I was going to do. My residency is where I first met a couple of nephrologists who are incredibly smart, fantastic folks, and then I came to the realization that the kidney disease population was basically that population I imagined I was going to take care of as a physician when I was young… So, I think a combination of academic interest in kidney disease and really seeing that there's this at-need population led me to really refocus on preventing and managing kidney disease.

And then ultimately, when I came back for my nephrology training, the gentleman who turned out to be my research mentor was one of the transplant physicians. So, then I learned about transplant medicine and [saw] for the folks whose kidney disease we can't prevent, here is this opportunity to really improve the lives of people who had end-stage kidney disease and that was really appealing to me.

Please tell us more about the "at-need populations."

I'm originally from Detroit, which has a large African American population. And when I was young, I recognized that there was sort of an excess of medical diseases in African Americans without, at 15 years old, being able to define that. And so now on the back end, I recognize that although kidney disease can impact everybody, we have some demographic groups that are disproportionately impacted, including African Americans, Hispanic individuals, Native Americans, among others, largely driven by these excesses of diabetes and high blood pressure that we see in these populations. As someone who's still in Michigan, I also recognize that we have rural populations that don't have great access to care, who are at higher risk for kidney disease, kidney disease progression.

What are some highlights or milestones from your career that stand out to you or that you're most proud of it?

There's a lot… Certainly my service to the American Kidney Fund has been really one of the highlights of things I've been able to do in my career, to work with really a fantastic organization that's involved in the community across the spectrum of kidney disease. I particularly like and appreciate the educational component of the work that the AKF does. So that's really been tremendous.

In my career on a day-to-day basis, I have had the opportunity to really see the impact of getting people transplanted. That we really have improved and extended people's lives. And you have people who are really struggling on dialysis, and you get them transplanted and I've been in practice long enough now that you have these same folks now have children or grandchildren or are doing all the life things that they may not have been able to do without a kidney [transplant]. So, that's probably the most important thing that I'm able to contribute to is this improvement in people's lives.

Then on a sort of policy side, I've done a lot of work with the with the OPTN [Organ Procurement Transplant Network]. During my time, I've had the opportunity to be part of efforts to update the transplant allocation system. There are some changes that are just part of the system now that have been to people's benefit that when I first became involved weren't part of it, and in working with a number of committees (because all the work we do is really team driven stuff), that really made some improvements that brought some fairness to patients and had big impacts nationally. So, it's been great to be involved with projects.

I had the opportunity to work closely with my nurses over the last two years with the eGFR modification that the OPTN put out – giving full credit to my nurses who really did the bulk of the work – we were able to modify a lot of eGFR's and transplant some 60-70 people over the year. Because we adjusted their waiting time based on eGFR and got a whole bunch of people, who are arguably disadvantaged, transplanted so it's been great to be involved in those projects as well.

And then just routinely, I've had the opportunity to be out in my local community, in the southeast Michigan community, just talking to different community groups and young people, trying to figure out how we keep them well-educated about kidney disease and minimize kidney disease. So, those have been some great events or opportunities that this career has afforded me.

What big changes have you seen in the nephrology field over the course of your career?

We have some new medications that are coming on board, we have seen improvements in how well people do with transplant, we have made the system fairer in the process of some updates and changes with the OPTN… if you look at the last 25-30 years, the system today is so much better than it was before because we have continuously recognized deficiencies in the system, unintended consequences of the system, and worked to correct those. So, there's been steady incremental improvement.

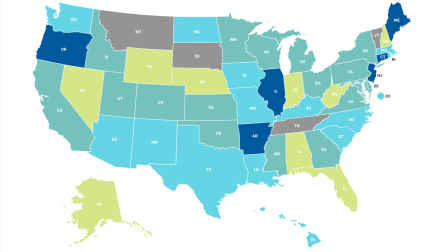

I think there has been increased recognition both of kidney disease in general and in the community, which is good. I think there has been increased recognition of the importance of timely transplant and the impact it can have. And we've seen multiple administrations' support for advancing transplant policies, which has been good. We have seen, through the efforts of a lot of really good people, a lot of improvement in terms of people registering as organ donors. When I first started in the field, we had a lot of articles about the registration rates and donation rates of African Americans and [asking] why were they low? But through the efforts of groups like MOTTEP… we now have registration rates that in many places (certainly in Michigan) exceed the representation in the population… So, this can be done by really engaging with communities. And I think one of the cool things at AKF has been this direct engagement with communities. Because I think that's where you can make these make these small changes that become big changes.

I think one of the most exciting things happening is this recognition and deliberate effort into better understanding kidney disease and better defining kidney diseases. I know at AKF, we have our Unknown Causes of Kidney Disease Project, which I think highlights [how] we have a whole bunch of people with kidney failure, and we don't really know why they have kidney failure, which limits [their] ability to do something about it… So, to better define [the cause for] that population helps us to understand both people's risk and better inform people, but also then to design specific therapies. It wouldn't have been possible in the past because we didn't have the genetic tools that we have nowadays, and so nephrology [in the next] 15-20 years is going to look so much different than it than it does today. And that's huge. It's exciting to think that in one career you would see this transformation of the field. I think that's super exciting and has potential to transform what we do.

What advice would you give to any aspiring nephrologist, especially for those who are people of color?

I'd say we need more nephrologists. With the growth of the end stage kidney disease population, we don't have enough physicians to take care of the growing population of people in need. It's really a tremendous field. We have the opportunity to really help people live better, be better, extend their lives, have better quality of life. So, it's incredibly rewarding to work hard and do well for people and overall have them do well. And there's a spectrum of what people can do, what people need from lab-based science through clinical research to clinical care to education to community-based work. Across the board, there are opportunities and needs that our kidney patients have that smart, interested people could help really play a meaningful part in.

Do you feel it's important for patients of color to see nephrologists of color as an option when they're considering their healthcare team?

I do. I do. Yes, it's certainly true that smart doctors can take care of anybody, but we know from what patients tell us that patients like to have the option to be cared for by people that look like them or have similar cultural experiences or speak the same language. [And] at the end of the day, I think it's about what will help this patient have the best outcome, and one of those things is the patient feeling as comfortable as possible and as open as possible. And a lot of that is seeing someone that they recognize or feel comfortable [that they have] something in common with [them]. And so, if you were taking care of a population about kidney disease, for instance, where folks are disproportionately Black, but we have a [scarcity] of Black physicians to take care of them, it doesn't give [patients] a lot of options. And we know that, across populations, across cultures, there are nuances, and it can be very helpful if you are either from that population or understand when people are making references.

One of the things we bring up a lot is like diet. When we're talking about modification of diet for kidney disease or for transplant and how to do that and how we're designing what we're asking people to eat, and we know that if we're not from different communities, sometimes the recommendations we make don't resonate. Because we don't quite get it, you know. And so, there's some opportunities that may not be apparent up front. I think about how can we better serve these patients. And some of that is looking the same or being from the same culture… So, I do think it's important. I think if you're going to serve a large population of whoever, it's nice to have the physicians, nurses, social workers – the care team look like the population you're serving in all those different ways that we think about it.